To be sure, global investment in civilian crisis management has grown a lot: from about €1 billion in 2004 to about €4 billion in 2019 (the last year with OECD data).

As part of their crisis spending, OECD members report specific investments in “peacebuilding and prevention.”

These investments have also grown a lot – but mostly before Guterres and other world leaders made their pledges in 2017.

If we separate acute crises from actual preventive cases, we find much lower figures:

In our estimate, global investment in aid for prevention was in the range of €650–820 million in 2019 – only marginally higher than in 2017, when world leaders signed on to Guterres’ prevention agenda.

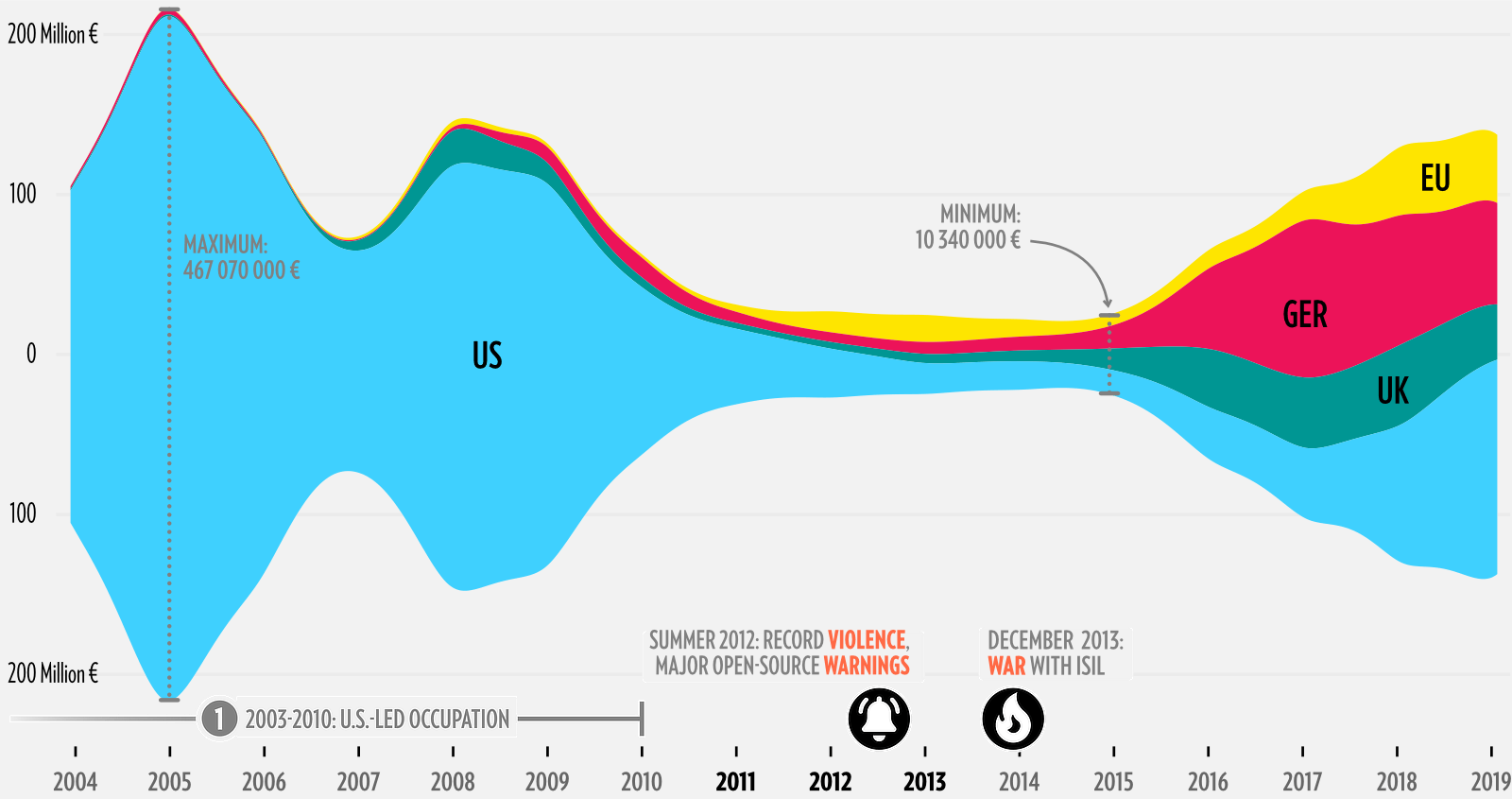

Important donors, most notably the UK, have even cut their spending, while Germany and the EU have driven a large portion of the most recent global expansion of investment.

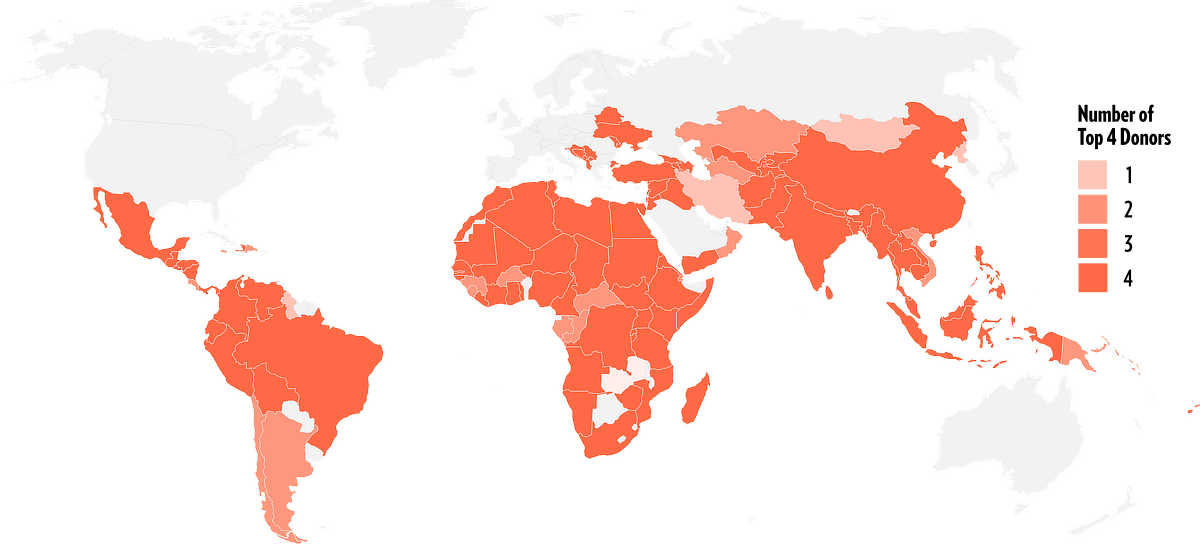

Peacebuilding and prevention investments rest on a small number of shoulders: the top four donors alone account for 68% of the global spend.

Germany is now by far the world’s largest peacebuilding and prevention donor in terms of official aid.

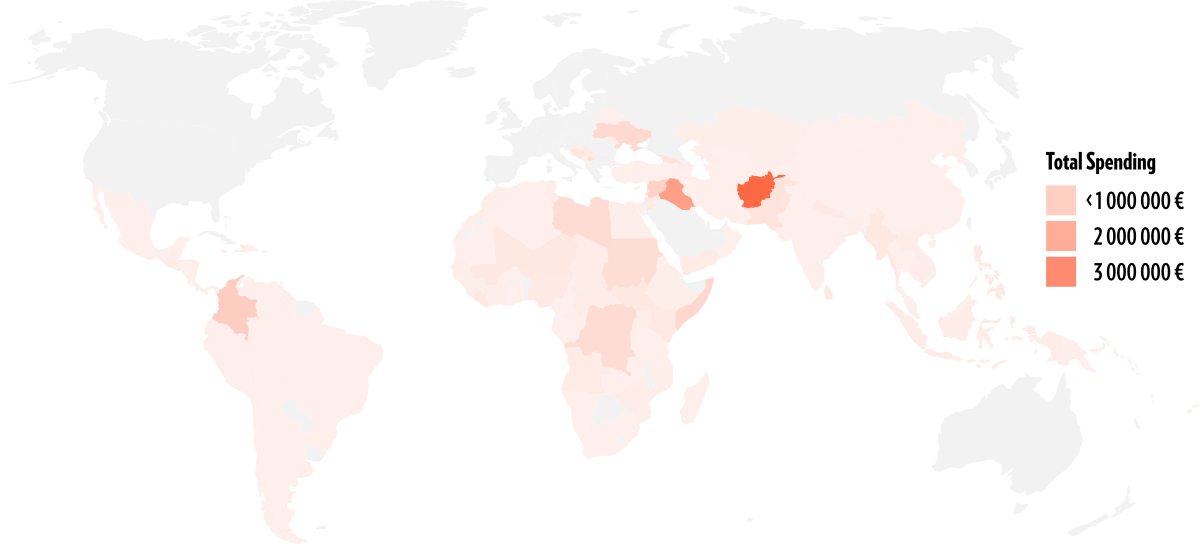

The top donors favor breadth over depth: up to 71 countries per donor receive money, but almost no country receives more than €1 million per donor – likely far too little to make a difference.

This falls far short of the €85–850 million per country per year, focused on a handful of countries with good prospects for preventive success, that the UN-World Bank model finds necessary for effective prevention.

Almost every country that receives prevention spending at all (orange), receives it from all four top donors (97%).

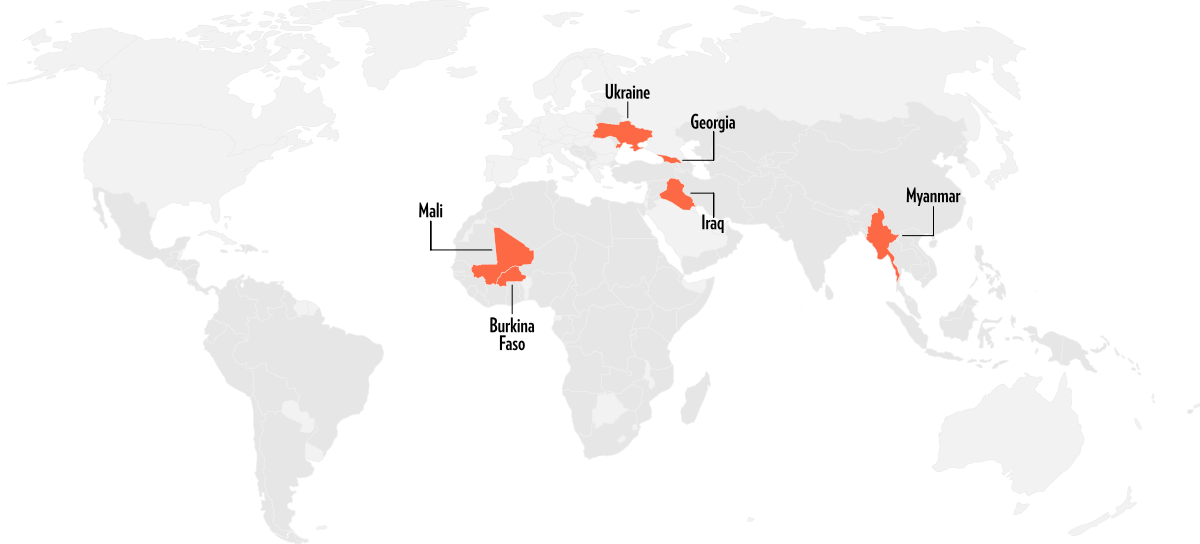

Beyond the aggregate data, we also developed another approach to identify preventive action based on the timing of projects in relation to early warning in six case studies from 2004 to 2019.

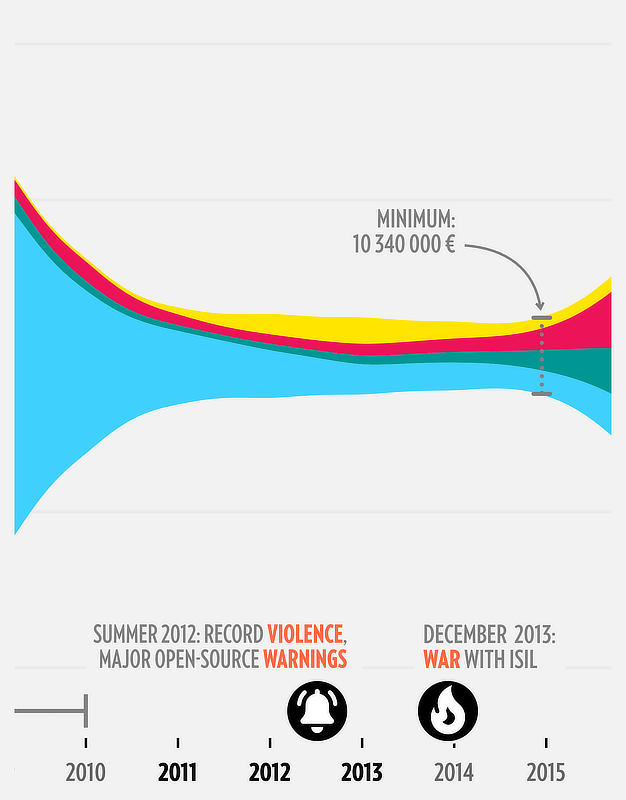

Take the example of Iraq: As the US withdrew their troops in 2010, the warning signs were well understood.

But Top Four donor investments in peace or prevention went down year after year. They only began to rise again a year after the war had re-started, when donors began to invest in stabilization.

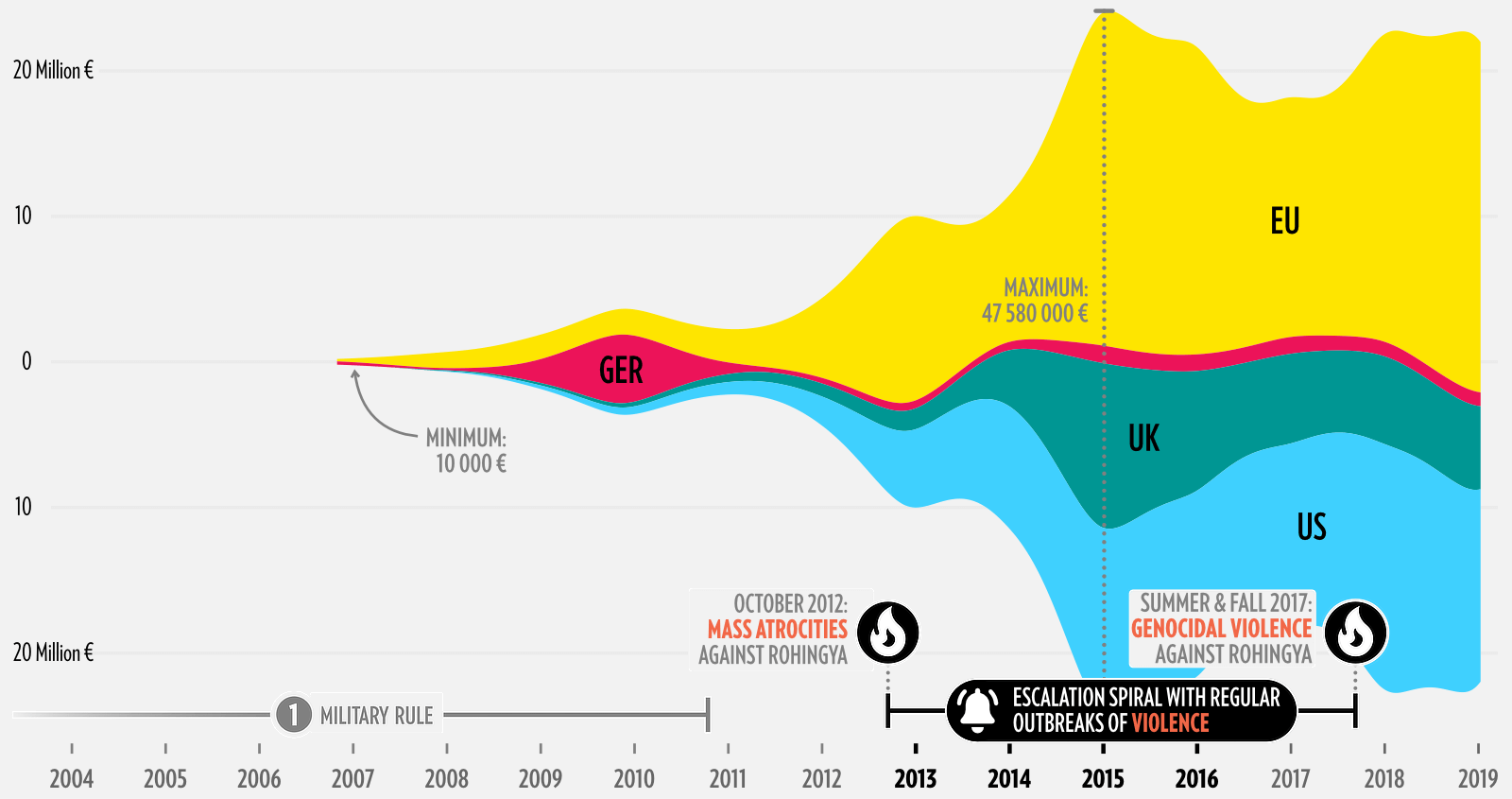

Or take Myanmar, for a slightly different finding:

The country has seen mass atrocities since at least 2012. Violence escalated in waves and reached the level of genocide by 2017.

Unlike in Iraq, three of the four top donors spent more for peacebuilding and prevention with each wave.

When we look into the project information, it appears as if the purpose of the increased spending was indeed to prevent further escalation and build peace.